Cameron Pitches / NZ Herald

During the debate about the forthcoming 5c per litre increase in petrol excise, a number of politicians and commentators have suggested deferring the increase until oil prices stabilise at lower levels. Yet no one has been able to offer a valid reason why prices should come down.

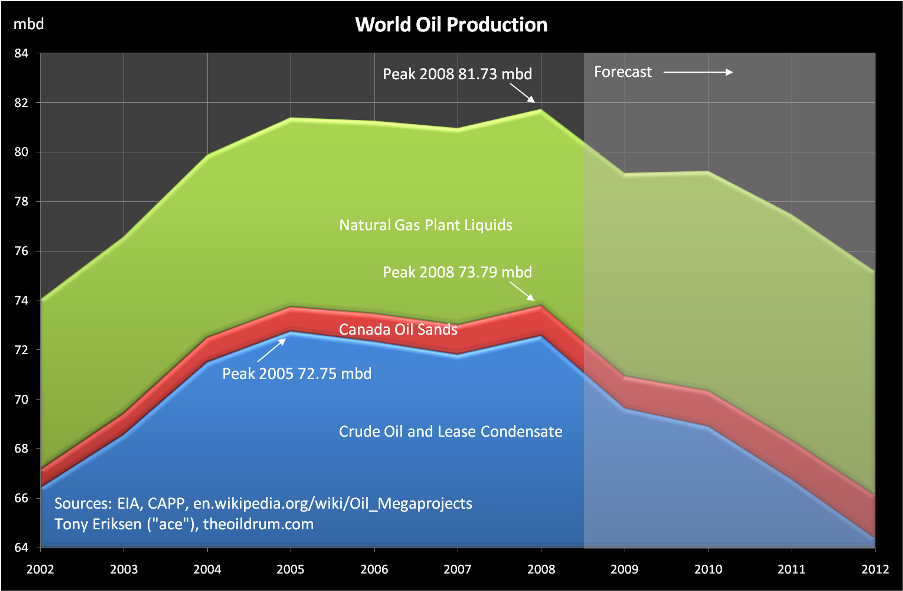

With global crude oil consumption running at a staggering 84 million barrels a day, the current price of around $US56 per barrel seems entirely reasonable. At an equivalent price in our currency of 50c per litre, even imported bottled water is more expensive.

Most people are aware that crude oil prices are currently at all time highs. Fewer people know why this is, and fewer people still have heard of a Shell Oil geophysicist called M. King Hubbert.

In 1956 Hubbert predicted, with considerable jeopardy to his career prospects, that oil production would peak in the United States some time between 1965 and 1972. In making this prediction he had determined that the production rate of oil follows a bell shaped curve. The variation in the timing of the peak reflected different estimates of known reserves of oil.

As it turned out it wasn’t until 1972 that analysts realised the peak had occurred two years earlier in 1970. Hubbert’s theory was proved correct. US oil production has declined ever since, so much so that today the US only produces about half as much oil as it did in 1970, roughly 5m barrels a day. No amount of future drilling can reverse this trend either. If the Arctic National Wildlife Reserve is opened up for drilling, the peak production from this environmentally sensitive area will only amount to an additional half a million barrels a day, in about 15 years from now.

Expanding his analysis to the global oil situation, Hubbert predicted in the late 1960’s that the global peak would be some time around 2000. His estimate has been further refined, notably by Princeton geologist and a former colleague of Hubbert’s at Shell, Professor Kenneth Deffeyes. His somewhat tongue-in-cheek prediction is 24th November, 2005 – Thanksgiving Day in the United States. Other projections range from “already peaked” to an optimistic 2035, which comes from the US Geological Survey.

Regardless of when the actual peak occurs, we are already living with high oil prices and associated high volatility. Over 50 countries are now producing less oil than they did a year ago, and discoveries of oil peaked in the 1960’s. Despite comments from OPEC about increasing oil production, there appears to be almost no spare production capacity at all. Qatar Oil Minister Abdullah al-Attiyah recently said that the current high prices are “out of the control of OPEC.”

Even with these high prices, demand for oil continues to go at unprecedented rates. China looks set to import 30% more oil than it did last year, and demand has also increased in almost every other country in the world.

The peaking of supply coupled with high demand growth can only lead to higher and higher oil prices for the foreseeable future.

Simply put, oil producing nations cannot get oil out of the ground fast enough to meet demand.

New Zealand’s transport agencies need a contingency plan for the rising price of oil. At $US70 a barrel, the Auckland Regional Transport Authority should be looking to secure options on electric rolling stock for our rail network. At $US100, Central Government should be suspending all new roading projects. At $US200, Auckland International Airport’s proposals for a second runway should be shelved in favour of a container wharf for shipping.

Reliance on emerging new energy technologies such as hydrogen won’t help us in the short term either. The so-called”hydrogen economy“ is a net energy loss proposition – more energy is put in to the extraction, compression and storage of hydrogen than comes out of it.

In addition, currently over 90% of all hydrogen is obtained from fossil fuels, which defeats the purpose of an alternative fuel. While hydrogen can also be obtained through the electrolysis of water, this process requires electricity and is 70% efficient. Adding the compression and storage requirements of hydrogen to the equation means that hydrogen is a net energy sink. These are just some of the significant hurdles to be overcome before we can look to hydrogen to solve our energy woes.

Nuclear power will not help us either. Significant environmental issues aside, uranium is subject to the same bell shaped production curve as oil, and evidence exists that it too may have reached its peak.

Alarmingly, in New Zealand it would appear that there is no contingency planning at any level of government for the likely prospect of high oil prices. The Government still retains a billion dollar investment in Air New Zealand. Treasury is still apparently sticking to its long term prediction of $35 per barrel. The ARC makes little mention of fossil fuel dependency in their Regional Land Transport Strategy. The 5c increase in petrol excise tax is to be spent on roading projects, when a better use of this money would be investing in research and development of energy sources and projects that do not rely on fossil fuels.

Other countries are beginning to accept that Hubbert’s Peak is inevitable. Queensland politician Andrew McNamara recently gave a speech on Hubbert’s Peak, concluding that “no alternative energy source available to us today or in the foreseeable future is going to make up the total energy shortfall.” In the US, Republican Congressman Roscoe Bartlett gave an hour long presentation to Congress on Hubbert’s Peak.

When Hubbert’s Peak becomes a reality, only the economies which are fastest to adapt to new energy sources will survive and prosper. New Zealand, with its near total reliance on fossil fuels coupled with poor contingency planning, does not look set to be one of these.